Let's play Brisca

In this article, we'll see how to use modern Prolog to model the game of Brisca. First things first, what is Brisca?

Rules of the game

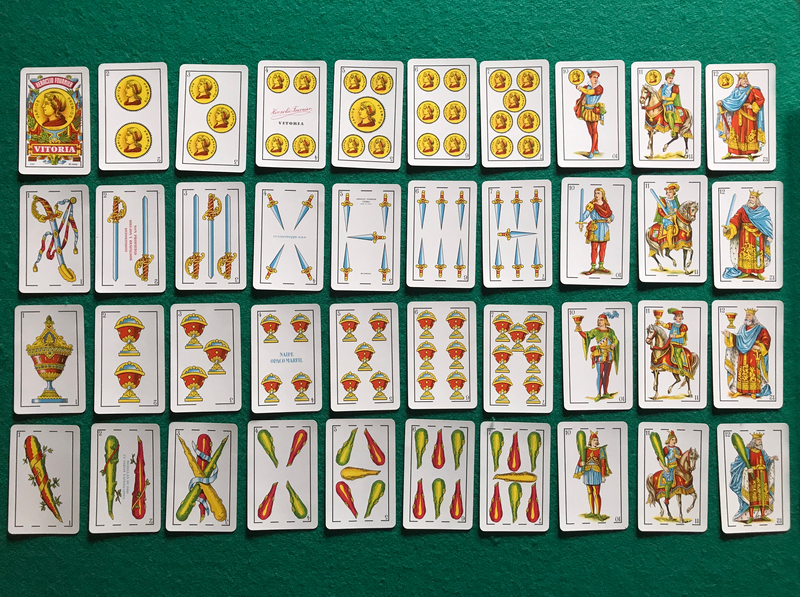

Brisca is a traditional card game from Spain, although similar games both in name and in rules are spread across the Mediterranean. It's also similar to Tute. It is played using the traditional Spanish deck, usually with 40 cards in 4 suites (oros, espadas, bastos, copas). Here you have the famous Castillian pattern by Heraclio Fournier, the one I play in my family with my grandparents.

How do you play it? Basically, players play in rounds. Every round each player on the table (usually four), selects one of his own three cards to leave one in the middle, and they do that in order. There are some rules, which I will explain later, and one person wins the round, taking all the cards with him. Players take new cards from the stock. Some cards get you points, some others don't. After there are no more cards in player's hands, we count the points, the players with more points, wins!

The rules for knowing which players takes the round are the following: - Every game there's a trump suite, which was selected as a random card from the stock at the same time when the players got their three initial cards. - The first player in a round (the winner of the previous round) can choose whatever card he wants. - The rest of the players, in order to win the round, they need to improve the card of the first player. They can put a higher card of the same suite as the first player. - Or they can put a card from the trump suite, which is always better than a card from a non-trump suite. - But between cards in the trump suite, there's still an order. - However players are not required to put cards that improve the game if they don't wish to do that, they can just lose the round to discard themselves a bad card. - The order is the following: As (ace, number 1) -> 3 -> Rey (king, number 12) -> Caballo (horse, but usually it's a knight, number 11) -> Sota (a page, number 10) -> 7 -> 6 -> 5 -> 4 -> 2.

Modeling cards

First, we need to decide a representation of our cards. Coming from another languages we can think that a good representation might be a class or a struct, with two fields, one for the number and the other for the suite, but Prolog doesn't have objects. We can use a list with two elements. But lists are better when we're dealing with variable length data. We could also use a compound term. This is the right choice if our fields are fixed.

A compound term is defined by an atom, followed by the data itself enclosed by parenthesis and separated by comma. Like this: card(oros, 4). Yes, very similar to predicates. In fact the only difference is how we use them, because they're the same. If we pass a compund term in the first level of a query, or inside a call/N, Prolog will treat it as code instead of data. This is one the the examples of Prolog being a homoiconic language.

We can go further, Prolog is very flexible and we can define custom operators easily if we want. Those are also compound terms, but with a different syntax. There's an operator already defined that is very useful for us: the dash. We can just join two pieces of data with a dash, and they'll be together in the same structure. This is usually called "pair".

So, using pairs we can model cards like this: oros-4, espadas-7.

We can code a predicate that defines valid cards:

card(Suite-Number) :-

member(Suite, [oros, espadas, bastos, copas]),

member(Number, [rey, caballo, sota, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, as]).Counting points

We are going to implement a counting predicate. The suite doesn't matter, only the number. First, we define a card_score/2 predicate which relates a card to a score and viceversa.

card_score(_-as, 11).

card_score(_-3, 10).

card_score(_-rey, 4).

card_score(_-caballo, 3).

card_score(_-sota, 2).

card_score(_-X, 0) :- member(X, [7, 6, 5, 4, 2]).Now, if we want to know how many points gives an specific card, we can ask:

?- card_score(oros-rey, X).

X = 4

; false.(Remember, to load a file named brisca.pl in Scryer Prolog, we can run scryer-prolog brisca.pl in your favourite shell.)

But we can also ask what cards can give you that value:

?- card(X), card_score(X, 11).

X = oros-as

; X = espadas-as

; X = bastos-as

; X = copas-as.You have probably noticed that I included the card predicate in the toplevel (which kind of acts like a type restriction), not in the card_score/2. However, does it make sense for cardscore to work on something that is not a also a card? Both approaches are valid if applied correctly. Some people prefer to set domain restrictions like this externally, as it allows you to write more concise code and it usually performs better. However, having a card predicate in `cardscore/2` is more correct since it's not possible to use that predicate in something that is not a card. We can choose either option thanks to Prolog being a dynamic language.

In my case, my final version is going to be a predicate which includes the card restriction and uses a wrapper predicate to have the short and concise code:

card_score(X, N) :-

card(X),

card_score_(X, N).

card_score_(_-as, 11).

card_score_(_-3, 10).

card_score_(_-rey, 4).

card_score_(_-caballo, 3).

card_score_(_-sota, 2).

card_score_(_-X, 0) :- member(X, [7, 6, 5, 4, 2]).Now we just need to work with a list of cards instead of a single card. This is a place where we can introduce DCGs. DCGs are the short name for Definite Clause Grammars, which is a shorthand notation used to describe sequences. We can use them to parse, generate, complete and check sequences in the form of lists.

We can define a base case. If there are no more elements in the sequence, the score should be zero. If there's a Card, we can calculate its score and sum it together with the rest:

cards_score_(0) --> [].

cards_score_(X) -->

[Card],

{ card_score(Card, X0), #X #= #X0 + #X1 },

cards_score_(X1).In DCGs, to match an item of the sequence, we use brackets. We use braces to introduce normal Prolog code. Calling other DCGs (in this case, the same, as it's a recursive one), it's just calling it again. Notice in this code that we are doing the addition of X0 and X1 when we still don't know the value of X1. This would be an error in the traditional arithmethic system of Prolog, but it's valid with clpz. clpz allows us to have a more declarative arithmethic, at least with integers.

Now we can try this code using phrase/2 which is needed to jump to a DCG.

?- phrase(cards_score_(X), [oros-as, oros-rey, oros-7]).

X = 15

; false.It seems to work. However there's a small problem. if we try to do the reverse, generating a sequence of cards that give you a specific amount of points, we'll find trouble. The program won't end. This is basically because be default we are not fair enumerating. This means that it will go deep into the recursion, trying to create an infinite length sequence. We need a way so that it does iterative deepening (starts with sequences of length 1, then length 2, ...). Luckily, if we pass our list first through the length/2 predicate, it will do exactly that. This is usually done at the outside.

cards_score(Cards, Score) :-

phrase(cards_score_(Score), Cards).

cards_score_(0) --> [].

cards_score_(X) -->

[Card],

{ card_score(Card, X0), #X #= #X0 + #X1 },

cards_score_(X1).So now:

?- length(X, _), cards_score(X, 15).

X = [oros-rey,oros-as]

; X = [oros-rey,espadas-as]

; X = [oros-rey,bastos-as]

; X = [oros-rey,copas-as]

; X = [oros-as,oros-rey]

; X = [oros-as,espadas-rey]

; X = [oros-as,bastos-rey]

; ...

?- cards_score(X, Y).

X = [], Y = 0

; X = [oros-rey], Y = 4

; X = [oros-caballo], Y = 3

; X = [oros-sota], Y = 2

; X = [oros-7], Y = 0

; X = [oros-6], Y = 0

; X = [oros-5], Y = 0

; X = [oros-4], Y = 0

; X = [oros-3], Y = 10

; X = [oros-2], Y = 0

; ...Winner of a round

Now, let's try to model the winner of a round in the game. First, we can model the pseudo-numerical order of the cards in a suite. We can start with a simple idea, if we have a list with the right order, we can take an element and see if the other card is in the higher section of the rest of the list.

card_higher_n(N0, N1) :-

Order = [as, 3, rey, caballo, sota, 7, 6, 5, 4, 2],

append(Highers, [N0|_], Order),

member(N1, Highers).This works well, and it can show all of the 'Y is higher than X' relationships:

?- card_higher_n(X, Y).

X = 3, Y = as

; X = rey, Y = as

; X = rey, Y = 3

; X = caballo, Y = as

; X = caballo, Y = 3

; ...For some people this might be enough. However, since we're in Scryer Prolog, we can also use reificated predicates. Using this technique, we can show not just the 'Y is higher than X' but also, the complete set of solutions of 'Y is NOT higher than X'. In order to do that we need to add a third argument to our predicate, which will be true or false (the predicate is true for the given X and Y or it's false). And we need to change member/2 to a reified version of it: memberd_t/3.

card_higher_n(N0, N1, T) :-

Order = [as, 3, rey, caballo, sota, 7, 6, 5, 4, 2],

append(Highers, [N0|_], Order),

memberd_t(N1, Highers, T).Now, we get for every combination a T truth value and also, in the case of false queries, we get the constraints that need to be held to get that result:

?- card_higher_n(X, Y, T).

X = as, T = false

; X = 3, Y = as, T = true

; X = 3, T = false, dif:dif(as,Y)

; X = rey, Y = as, T = true

; X = rey, Y = 3, T = true

; X = rey, T = false, dif:dif(3,Y), dif:dif(as,Y)

; X = caballo, Y = as, T = true

; X = caballo, Y = 3, T = true

; X = caballo, Y = rey, T = true

; X = caballo, T = false, dif:dif(3,Y), dif:dif(as,Y), dif:dif(rey,Y)For example, if X = 3 and Y = as, then Y is higher than X. But if Y is different from as, then it's false.

Using reified predicates can be wise if we want to raise ourselves to a more declarative way of working with Prolog, but it's newer and not applicable form some problems. In this case, it's fine, so we'll use them.

Now, to model the relatioships of whole cards, we need to take into account the suites too. We're going to compare the suites, if they're the same, we just apply the pseudonumerical order. If they're different we check if the suite of the supposedly higher card is the trump suite. We can continue to use reified predicates from library(reif) like if_/3, which takes a reified predicate as a condition and =/3 which does reified unification. We also expose our T truth argument in this predicate:

card_higher(Trump, Card, Higher, T) :-

card(Card),

card(Higher),

Card = S0-N0,

Higher = S1-N1,

if_(S0 = S1,

card_higher_n(N0, N1, T),

=(S1, Trump, T)

).The code allows us to generate every card combination with every trump value and their truth value:

?- card_higher(Trump, X, Y, T).

X = oros-rey, Y = oros-rey, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-caballo, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-sota, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-7, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-6, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-5, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-4, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-3, T = true

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-2, T = false

; X = oros-rey, Y = oros-as, T = true

; Trump = espadas, X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-rey, T = true

; X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-rey, T = false, dif:dif(espadas,Trump)

; Trump = espadas, X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-caballo, T = true

; X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-caballo, T = false, dif:dif(espadas,Trump)

; Trump = espadas, X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-sota, T = true

; X = oros-rey, Y = espadas-sota, T = false, dif:dif(espadas,Trump)For example a espadas-caballo is higher than oros-rey if Trump = espadas, otherwise, it isn't.

Now, let's check for the winner. For every card we need to check if the current one is higher value than the current highest. It's very easy, we just need to to do a fold! Just like in functional programming, we have a fold predicate. Actually, it's a fold-left, but for this case we need the right order, so we will need to reverse the list first. The, for our foldl, we're going to use a lambda predicate from library(lambda).

This library, allows us to write unnamed predicates that are very useful in metapredicates like foldl/4. The syntax might be a bit confusing if you're coming from other languages as it's a bit unique. You can find the complete description of the syntax in the documentation page.

The code looks like this:

round_winner(Cards, Trump, WinnerCard) :-

reverse(Cards, [FirstCard|RestCards]),

foldl(Trump+\X^Y^Z^if_(card_higher(Trump, X, Y), Y = Z, X = Z), RestCards, FirstCard, WinnerCard).

?- length(Cards, 4), round_winner(Cards, Trump, Winner).

Cards = [oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-caballo,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-sota,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-7,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-6,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-5,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-4,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-3,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-3

; Cards = [oros-2,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [oros-as,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = oros-as

; Cards = [espadas-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Trump = oros, Winner = oros-rey

; Cards = [espadas-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey,oros-rey], Winner = espadas-rey, dif:dif(oros,Trump)A complete game

Now we have the basic pieces of the game. But we don't have a complete game. A game starts with someone dealing the first three cards to each player, a trump suite is selected, then we start the rounds: players put one card each, we choose a winner, the winner takes the cards and players get a new card from the stock. This all seems very procedural, but we're using Prolog. What can we do about it?

Let's ask ourselves what is a procedure. It's a sequence. And we have already seen a way to describe sequences in Prolog! The DCGs.

The basic idea however is having explicit states. The predicates that we're going to write will take an state (a view of the world at a certain point) and will give us the next state.

Let's define the state first. In a game of Brisca we have players. Each player has the three cards he can choose to put (less if we're running out of cards) and the cards he has got from winning rounds. Aditionally we have a stock, a trump suite and the order to play, which is usually from the player who won the last round and going to the right. We could store the data in a list, with different compound terms:

[players([player(Name, PlayableCards, WonCards), player(Name, PlayableCards, WonCards), ...]), stock(Cards), trump(Trump)]In order to express states using DCGs, we can use semicontext notation:

state(S), [S] --> [S].

state(S0, S), [S] --> [S0].So, for example our predicate to reset the game, and leave all the different cards in the stock would like this:

reset -->

state(_, [stock(Cards)]),

{

setof(Card, card(Card), Cards)

}.To shuffle them:

shuffle_cards -->

state(S0, S),

{

select(stock(Cards), S0, S1),

shuffle(Cards, ShuffledCards),

S = [stock(ShuffledCards)|S1]

}.Where shuffle/2 is a predicate that implements the Fisher-Yates algorithm in Prolog:

shuffle([], []).

shuffle(Xs0, [Y|Ys]) :-

length(Xs0, N),

random_integer(0, N, R),

nth0(R, Xs0, Y, Xs),

shuffle(Xs, Ys).We can also code more specific state accessors, which could be useful to know which part of the state each predicate can modify:

players(P0, P), [S] -->

[S0],

{ select(players(P0), S0, S1), S = [players(P)|S1] }.The whole state management topic in DCGs could be the whole topic for another article.

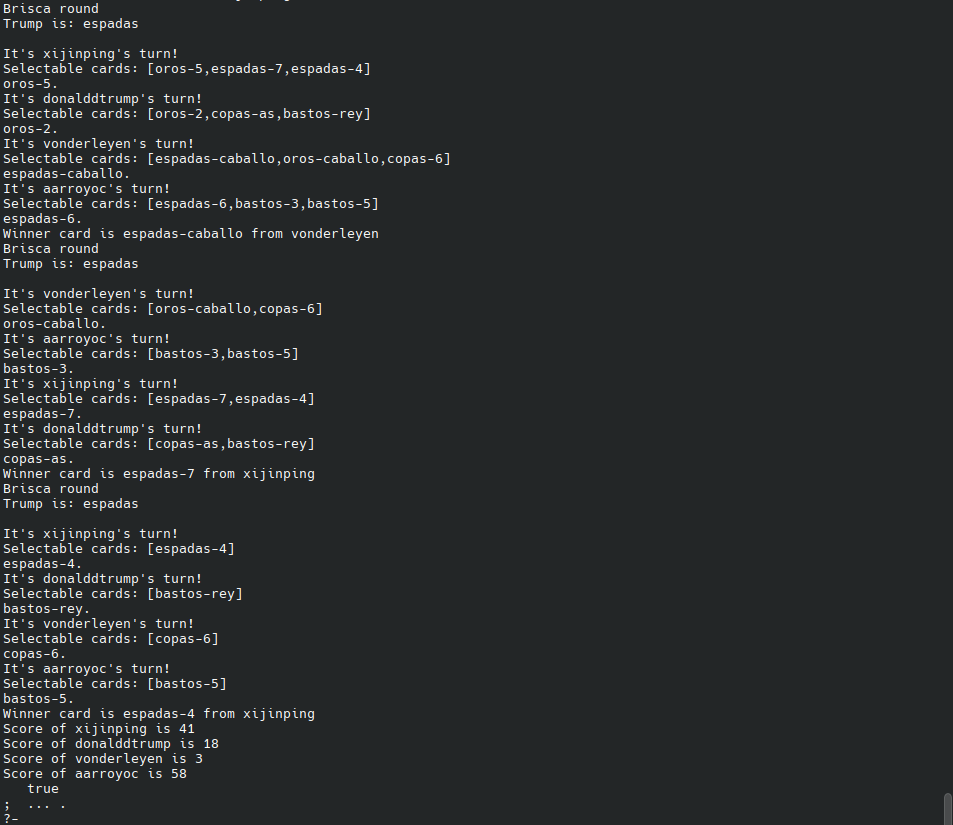

The final DCG code for an interactive version of Brisca could be as follows:

brisca :-

phrase(brisca, [_], [_]).

brisca -->

reset,

shuffle_cards,

set_trump,

create_players([aarroyoc, xijinping, donalddtrump, vonderleyen]),

play_rounds,

show_scores.

reset -->

state(_, [stock(Cards)]),

{

setof(Card, card(Card), Cards)

}.

shuffle_cards -->

state(S0, S),

{

select(stock(Cards), S0, S1),

shuffle(Cards, ShuffledCards),

S = [stock(ShuffledCards)|S1]

}.

set_trump -->

state(S0, S),

{

member(stock(Cards), S0),

length(Cards, N),

nth1(N, Cards, LastCard),

LastCard = Trump-_,

S = [trump(Trump)|S0]

}.

create_players(Names) -->

state(S0, S),

{

same_length(Players, Names),

maplist(\N^X^(X=player(N, [], [])), Names, Players),

S = [players(Players)|S0]

},

deal_one_card_per_player,

deal_one_card_per_player,

deal_one_card_per_player.

deal_one_card_per_player -->

state(S0, S),

{

select(players(Players), S0, S1),

select(stock(Cards), S1, S2),

deal_one_card_per_player(Players, Players1, Cards, Cards1),

S = [players(Players1), stock(Cards1)|S2]

}.

deal_one_card_per_player([], [], Cs, Cs).

deal_one_card_per_player(Ps, Ps, [], []).

deal_one_card_per_player([P|Ps], [P1|Ps1], [C|Cs], Cs1) :-

P = player(N, A0, B0),

P1 = player(N, [C|A0], B0),

deal_one_card_per_player(Ps, Ps1, Cs, Cs1).

play_rounds -->

players(P, P),

{ P = [player(_, X, _)|_], length(X, 0) }.

play_rounds -->

players(P, P),

{ P = [player(_, X, _)|_], length(X, N), N > 0 },

play_round,

play_rounds.

play_round -->

state(S),

players(P0, P2),

{

member(trump(Trump), S),

format("Brisca round~nTrump is: ~a~n~n", [Trump])

},

play_players(P0, Cards),

{

round_winner(Cards, Trump, WinnerCard),

maplist(remove_card, P0, Cards, P1),

nth0(N, Cards, WinnerCard),

nth0(N, P1, WinnerPlayer0),

append(PBefore, [WinnerPlayer0|PAfter], P1),

WinnerPlayer0 = player(WinnerName, C, W0),

format("Winner card is ~w from ~w~n", [WinnerCard, WinnerName]),

append(W0, Cards, W1),

append([player(WinnerName, C, W1)|PAfter], PBefore, P2)

},

deal_one_card_per_player.

remove_card(P0, C, P) :-

P0 = player(N, C0, W),

select(C, C0, C1),

P = player(N, C1, W).

play_players([], []) --> [].

play_players([P|Ps], [C|Cs]) -->

{

P = player(Name, SelectableCards, _),

format("It's ~a's turn!~n", [Name]),

format("Selectable cards: ~w~n", [SelectableCards]),

read(C),

member(C, SelectableCards)

},

play_players(Ps, Cs).

play_players(Ps, Cs) --> play_players(Ps, Cs).

show_scores -->

players(P, P),

{

maplist(\X^(

X=player(N,_,Z),

cards_score(Z, Y),

format("Score of ~w is ~d~n", [N, Y])), P)

}.Now, we can play! Of course, if you substitute interactive choosing (via read/1) with another method, you could simulate games, try AI strategies, etc